Advanced Tutorials

Master complex prompts to generate interactive stories, self-marking forms, AI personas, and full project plans.

The Human in the Room

The complete guide to AI for teachers. Go beyond the tutorials.

Get the Book →3.1 Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Style Activity

This is one of my favourite uses of AI in education, but it comes with a caveat. If your students are under 13, they won't be able to use a large language model themselves at all; and if they are between 13 and 18, they will need parental permission to do so. But a way around this is to do this activity yourself on the board in front of the class, and ask your pupils to interact with the activity by using you as a medium to write the answers.

For those of you not familiar with choose-your-own-adventure activities, these are originally a book genre where the reader could make some decisions along the story, and each decision would lead to a different ending. On paper, the reader was asked to move to different pages in the book as the story progressed. For example: "If you chose A, go to page 51. If you chose B, go to page 11." This has a resemblance with role-play games and video games, and it facilitates that the reader immerse themselves in the narrative, normally by using the second person and addressing them as the main character of the story.

Apply all this to a large language model, and you will be quick to see the potential of such activities for the education sector. The most sound uses are in foreign languages, history, geography, English, and all the subjects where the narrative and the context can help pupils understand the content. But it also works in more practical subjects like maths, where you can ask pupils to solve problems to progress in the story.

When it comes to prompting, there is some good news for you: large language models already know what choose-your-own-adventure stories are about, so you won't have to describe thoroughly the genre. However, like in the case of every other educational activity, you will need to specify the role, the goal, the audience, the subject, the topic, etc. For example:

Sample prompt:

"Act as a teacher of economics and a specialist in the Great Depression. I need you to create an interactive choose-your-own-adventure story for my Year 12 economics students to interact with you and learn about the consequences of the stock market crash of 1929. They will be able to choose between three characters at the beginning of the story: a trader, a business person, and a worker. In each of your outputs, you will include a short paragraph to contextualise the story, followed by a question that the pupil or user will need to answer in order to progress in the story. The activity will last at least 10 of such exchanges, with your last intervention being an ending to the story, closed by the phrase THE END. Use a language that my Year 12 pupils can understand, but don't hesitate to include technical concepts if they are appropriately explained."

As you can see, I've included lots of specific instructions to signal how I want the interactions to be, the language that needs to be used, etc. Depending on the objectives of the task and your group, all these specificities can be changed to adapt them to your class and subject.

This is the LLM’s first response to my prompt:

Alright — let’s turn the Great Depression into an interactive journey your students can explore. I’ll start with the introduction and the first decision point.

📜 Introduction

It’s late October 1929. The United States has just experienced a shocking event — the Stock Market Crash. After years of economic growth during the “Roaring Twenties,” share prices have suddenly plummeted. Millions of dollars in paper wealth have vanished in a matter of days. Confidence in the economy is shaken, and the effects are starting to spread. No one knows exactly how bad things will get, but the crash has set the stage for what will later be called The Great Depression — the worst economic downturn in modern history.

You are about to step into the shoes of someone living through this crisis. Your choices will affect how you survive — or fail — in these turbulent times.

Choose your character:

- A Wall Street Trader — You live and breathe the stock market. You’ve made big money during the boom, but now your investments are collapsing.

- A Small Business Owner — You run a shop in a busy town. Customers are the lifeblood of your business, but fewer people are spending money.

- A Factory Worker — You earn a weekly wage in a manufacturing plant. You’ve heard rumours of layoffs and pay cuts.

Question: Which character will you choose to begin your journey?

3.2 Self-Marking Quizzes for Forms

We have seen in section 2.1 how to ask the large language model to generate multiple-choice quizzes. But what if I told you that by adapting the instructions a little bit, you can get a document ready to import from Google Forms or Microsoft Forms for you to turn into a self-marking quiz? I will start with Microsoft Forms.

To generate a self-marking quiz with Microsoft Forms using a large language model, you will need to follow the same instructions I listed when I discussed generation of quizzes. But you will need to add some specificities about the format and structure of the large language model output, and even better, a template. The structure of the quiz needs to be: question, followed by A, B, C, D options (or however many you would like to include), followed by an answer or ANS and the letter of the correct choice like this:

ANS: B

This is the complete prompt:

“Act as a teacher of history. Generate a 10-question multiple-choice quiz with four options per question for my Year 11 class on the topic 'Battle of Hastings'. We have been learning about this topic for the last week, and the purpose of this multiple-choice quiz is to check whether my pupils have learnt the fundamentals or we need to consolidate the content. The structure of the quiz needs to be: question, followed by A, B, C, D options, followed by an answer or ANS and the letter of the correct choice following this format: ANS: A.”

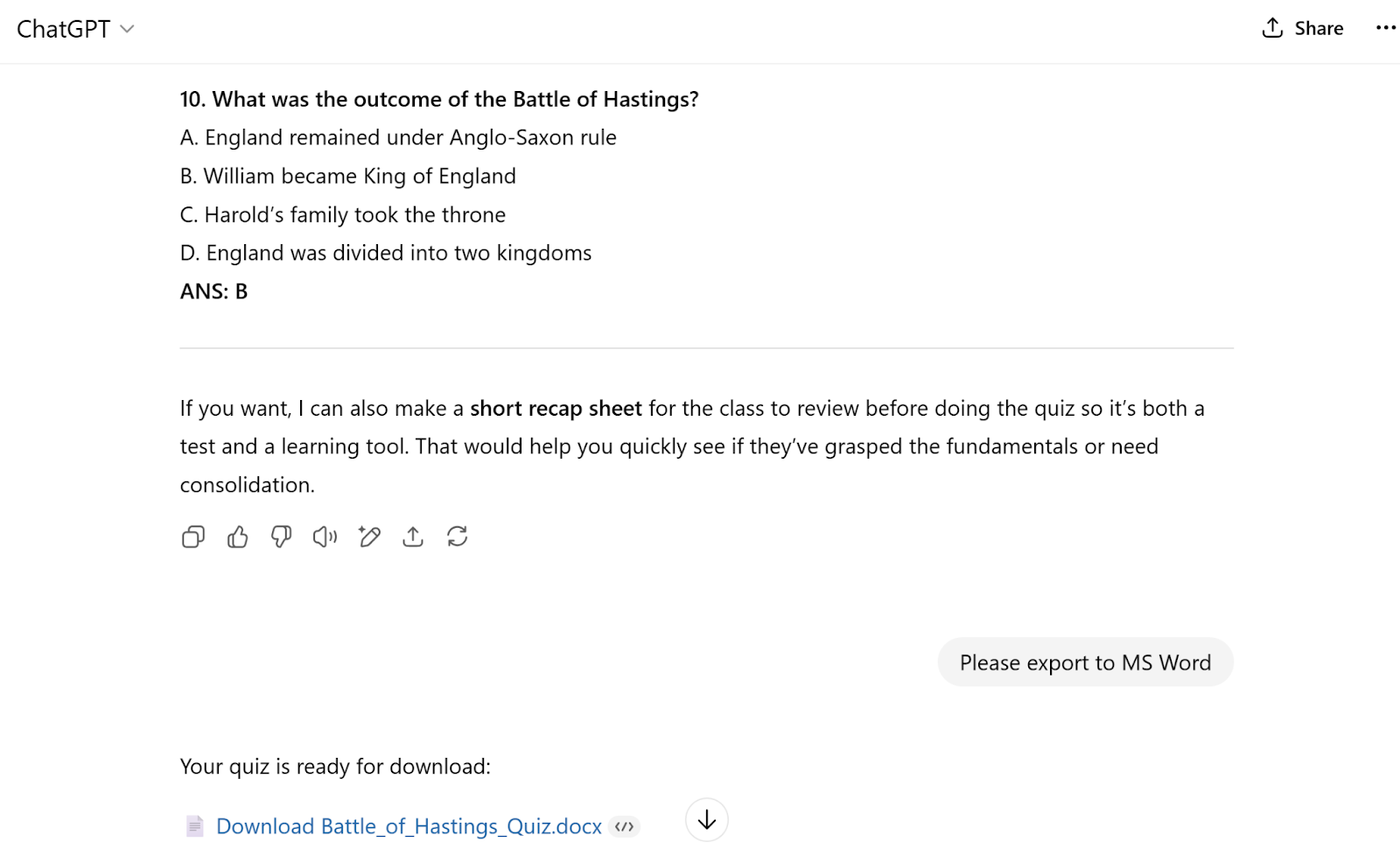

If you are using ChatGPT, you can simply ask the large language model to export this quiz to a Microsoft Word document (see figure 3.2.1).

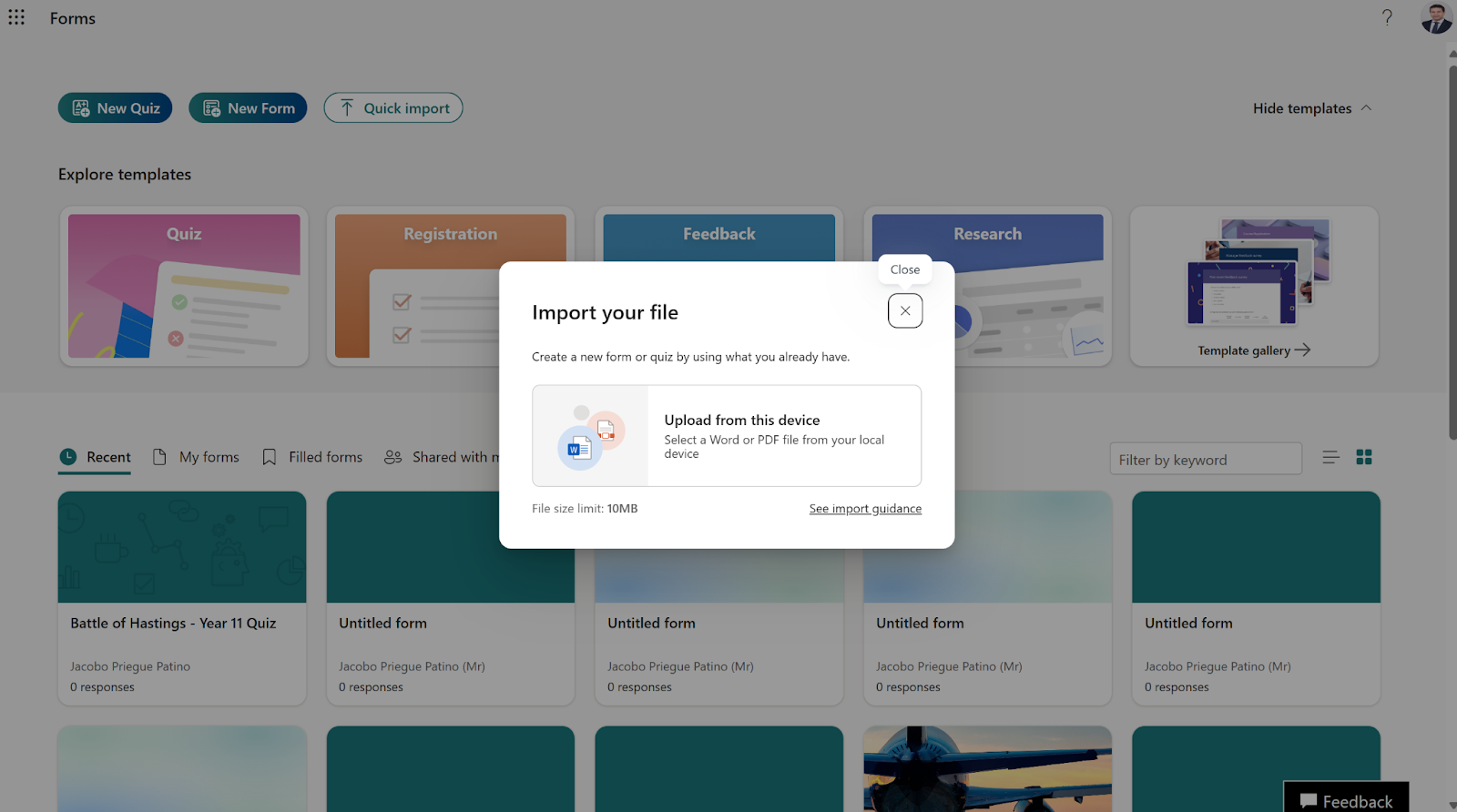

If not, you will need to copy-paste the large language model outcome into a Word document yourself and save it to your computer or device. Once you've got this document ready, you will need to go to the Microsoft Forms site and, in the top left corner, click on "Import." Then you will be prompted to choose between "Form" or "Quiz." You will need to select "Quiz" after you have chosen the file you want to import (figure 3.2.2.)

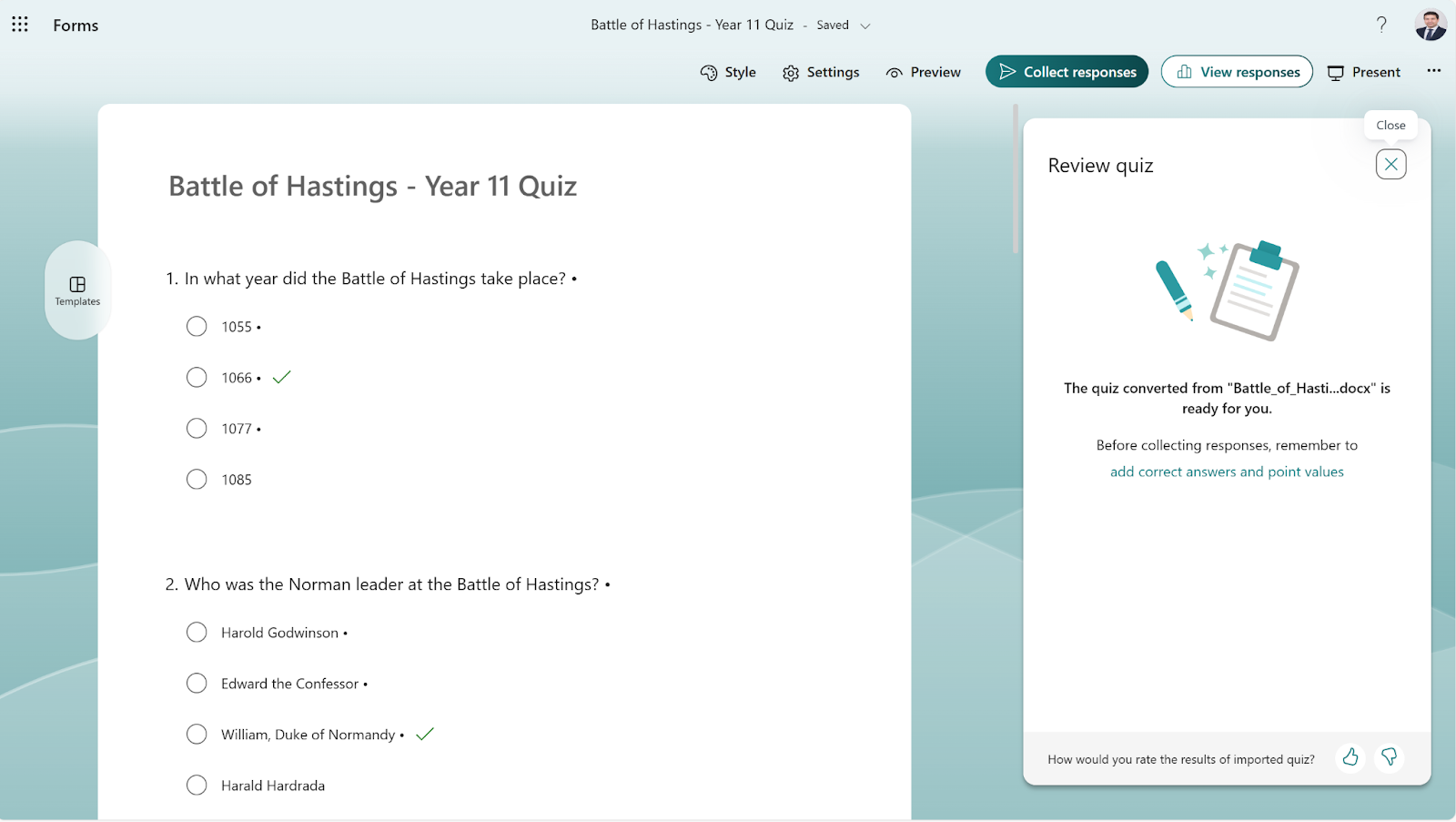

When it's done, simply click on "Review Quiz," and you will see that your quiz is already nicely formatted and including the right choice at the bottom for each of the questions. The only thing you need to do now is to assign a mark or point to each of the questions, since this is not done automatically. If you distribute these types of quizzes via Teams in the form of a quiz assignment, your students' marks will automatically be shown in your gradebook on Teams (figure 3.2.3.)

3.3 Worksheets

It is possible to generate full-length worksheets with a large-length model by crafting a well-structured prompt with enough level of detail. Worksheets are excellent for both homework and classwork, and they help pupils consolidate the knowledge that has been covered in lessons.

There are plenty of websites and platforms offering worksheets online, but if, like me, you sometimes struggle to find the right resource for your class, having a pre-made prompt for you to enter into a large language model will enable you to create however many worksheets in a matter of minutes. But to get exactly what you want, you will need to combine all the instructions we have been seeing in previous chapters with very detailed notes about the structure you want, for example: the type and number of activities, and the nature and number of exercises per activity. Headings and numbering will be your allies here, and the large language models will respond very well to this type of detail in your requests.

So, rather than just mentioning the activities you want, you will have to provide a clear structure for the large language model to follow. Let's use an example that has consistently worked for me in foreign language teaching. Start with the basics:

Sample prompt:

"Act as a teacher of Spanish. I need you to create a worksheet for my Year 10 pupils to consolidate the difference between the imperfect and preterite tenses and practise the conjugation of both regular and irregular verbs on the topic 'My Primary School and My Secondary School,' where they are comparing their lives then and now. I need you to include the following activities using the structure I provide here:

1. Vocabulary match up. Provide a list with 10 challenging words appropriate to this level of GCSE Spanish and the translation into English in a table. I need you to provide the Spanish words on the left column and the English words in a randomised order on the right. Make sure you include at least five verbs.

2. Fill in the gaps. Provide 10 sentences where one preterite and one imperfect tense verb are used, but instead of the conjugated form, provide a gap followed by the infinitive in brackets for the students to fill in with the correct conjugated form.

3. Multiple choice. Provide 10 sentences with one conjugated verb each. For each of the sentences, offer two options, one in the imperfect tense and one in the preterite, for the students to highlight the correct options. Make sure you randomise the order so preterite and imperfect don't follow a logical order like alternative sentences.

4. Translation. Provide five sentences in English for the pupils to translate into Spanish. Ensure there are examples of imperfect or preterite tense verbs in each sentence (not necessarily both in the same sentence) and that the vocabulary is suitable for this level of GCSE Spanish.

5. Sentence matter up. I need you to take 10 sentences and break them into two halves, ensuring the separation between the two halves is not always in the same place grammatically speaking (for example, before a connective or after a verb), but ensuring the separation spot is varied. Distribute the 10 first halves in the left column and place the other halves on the right column on a table. Ensure the second column is randomised so no left and right halves match in any given row."

As you can see, the level of detail is much greater than in other prompts, due to the nature and complexity of the task we are asking the large language model to perform. The good news is that once I have this pre-made prompt, I can now change the subject, the topic, the year group, or however many details I want to change, and create any worksheet in seconds. As usual, if we are not happy with one or several of the activities in the large language model output, we can iterate and refine as much as we need to.

To see the LLM’s output and what the worksheet looks like after being exported to MS Word, please see my video tutorial ‘3.3. Worksheets’.

3.4 Escape Rooms

Escape rooms are excellent activities because they offer all the advantages of a project-based learning experience with a fun twist, where the pupils compete in groups to break a code or put together all the pieces of a puzzle. The complexity here lies within the activities or tasks you will need to create for the pupils to unlock the next stages in a linear progression or to gather each piece of the puzzle in a non-linear progression.

We will follow the same steps as we did with the project-based learning experience, so I'm not going to discuss them in detail in this section; but once you've got your learning objectives clear and you have brainstormed ideas for your escape room with the large language model, you can start figuring out how your pupils will be able to get the pieces of the puzzle or to advance to the next stages. If you've got the capability, you can use numeric padlocks, safe boxes, etc., for the pupils to enter combinations. If not, they can run the answers through you, who will check whether they are correct or not, so you can give them the next hint, one of the pieces of the puzzle, or one number for the final combination.

Now you can simply use the large language model to create the different tasks in the escape room following the instructions and prompts we have been discussing in this chapter. In the next section, ‘Level 4: Expert’, I will show you how to turn escape rooms or any other activities into interactive web apps or videogames.

Sample prompt:

“Act as a secondary school teacher of history and educational designer. I need you to create an escape room activity for my Year 10 class. The main learning objective is to consolidate the pupils' knowledge of the main causes of World War I. The escape room will be linear, so pupils will need to complete the tasks in order to be able to progress. The final task will be to put the pieces of the puzzle together to get a code that will allow them to 'escape the room'. I need you to create four different tasks for this escape room, each of them in the form of a cloze activity, vocabulary questions, multiple choice questions, gap fill, one-word answer, etc. The four tasks must be related to the four main causes of World War I: militarism, alliances, imperialism and nationalism. For each of the four tasks, I need you to provide the instructions for the pupils and the solution. At the end, you will compile all of them and generate all the necessary handouts for the activity.”

LLM’s response:

Alright — let's design your Year 10 escape room so that it’s both historically rigorous and fun enough to keep them scrambling for the final “escape” code.

Escape Room: “The Great War Challenge”

Learning Objective: Consolidate knowledge of the four main causes of World War I: Militarism, Alliances, Imperialism, and Nationalism.

Format: Linear sequence — pupils must complete Task 1 → Task 2 → Task 3 → Task 4 in order. When they complete each task correctly, the teacher hands them one piece of the final puzzle (e.g., a slip of paper with a number). At the end, they assemble these pieces to form the final escape code.

Task 1 — Militarism (Cloze Activity): Pupils fill in gaps in a paragraph about the arms race.

Task 2 — Alliances (Matching): Pupils match the Triple Alliance and Triple Entente to their member countries.

Task 3 — Imperialism (Multiple Choice): Pupils answer two questions about colonial rivalries.

Task 4 — Nationalism (One-word answer): Pupils identify the "powder keg of Europe" and the "Black Hand".

Final Escape: Pupils assemble the four numbers to form the final code (e.g., 7429).

Teacher Handouts

Student Handout: A single sheet containing all four tasks for the students to complete.

Teacher Answer Sheet: Provides all solutions and the example puzzle pieces and final code.

If you’d like, I can also make this into a print-ready PDF escape room kit with stylised task sheets, answer boxes, and separate “puzzle piece” slips you can cut out for the students. That way, you can walk into class and run it straight away.

3.5 Customised Chatbots

The first time I thought about paying for a premium subscription with ChatGPT was when OpenAI released the GPTs. GPTs are customised versions of the large language model in which you can embed custom instructions or prompts so they always behave in a certain way.

I created dozens of them in the first month of my subscription, and I learned how to optimise them so they met my needs and my pupils'. The process wasn't as straightforward when the GPTs were released, and it took some trial and error to understand their behaviour based on a set of instructions; but after some training, I managed to create some very useful examples that range from the most simple quiz generator to the more complex ones that use code to generate web apps with games or Kahoot and Blooket template generators. Other ideas for custom chatbots are subject specialist assistants, worksheet generators, smart goals and rubric generators, speaking assistants for languages, and pretty much any use or prompt you can think about, because these custom chatbots are precisely that: a friendly wrapper for a good prompt or template.

Apart from OpenAI's GPTs, Gemini also offers the possibility to create custom chatbots, which they call "Gems." The principles are identical to those of ChatGPT, and nowadays, both versions have improved their functionality.

To create these custom large language models, you will need a premium account with either ChatGPT or Google Gemini. On the top left corner of the user interface, you will find, above your past conversations with ChatGPT, a button with the caption "Explore GPTs." There you can access the GPT store, where you can find the GPTs other users have created, and you will also find the option to create your own.

Once you click on it, a different interface will appear, and you will be prompted to enter the name of the GPT, a brief description, and your custom instructions. You can even add your own files and documents for them to be part of the chatbot's knowledge, and you can enable Code Interpreter, which will allow your custom chatbot to write and run code (for example, to export your chat or output to a Word document). In the instructions window, you will need to enter your prompt using the templates and techniques I have been discussing in previous chapters of this book.

Another feature you will see is the possibility to create an image or icon for your chatbot. This can be generated by ChatGPT itself or can be uploaded by you if you would like to use any custom images that you already have. Once you are happy with the name, description, image, instructions, and documents, you can now try your chatbot or save it to use it straight away.

Depending on the complexity of the instructions you have given, you will probably need to come back to tweak them after you have seen the results of your conversations. This can be a tedious process, but if you use the instructions I have discussed in this book, and if you are specific and thorough enough, you will be able to get the results you want much sooner.

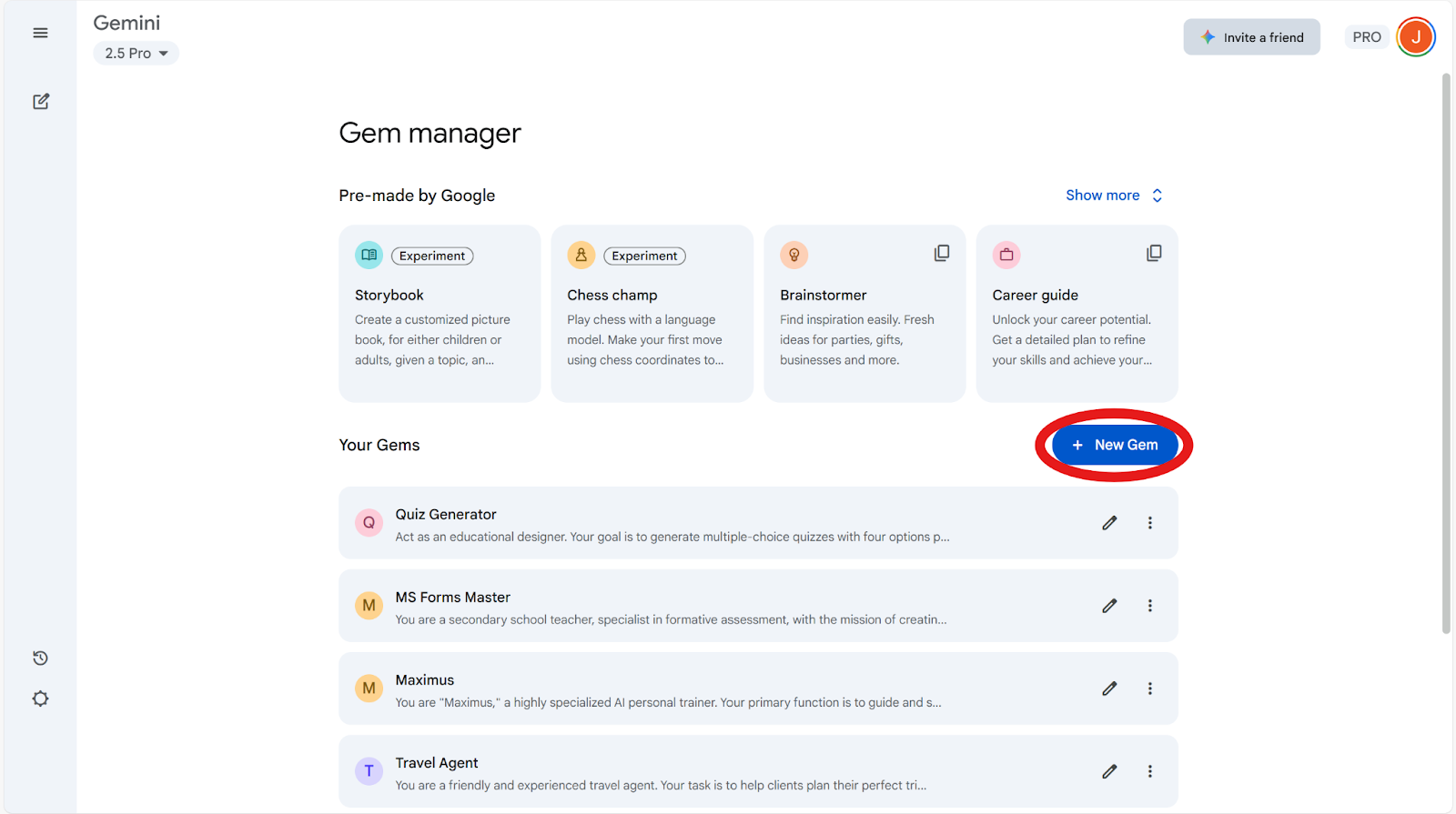

This is what the process looks like using Google’s Gemini. First, you need to click on ‘Gems’ in the left dashboard to display the Gems screen. Here, you will simply have to click on ‘New Gem’ (figure 3.5.1.)

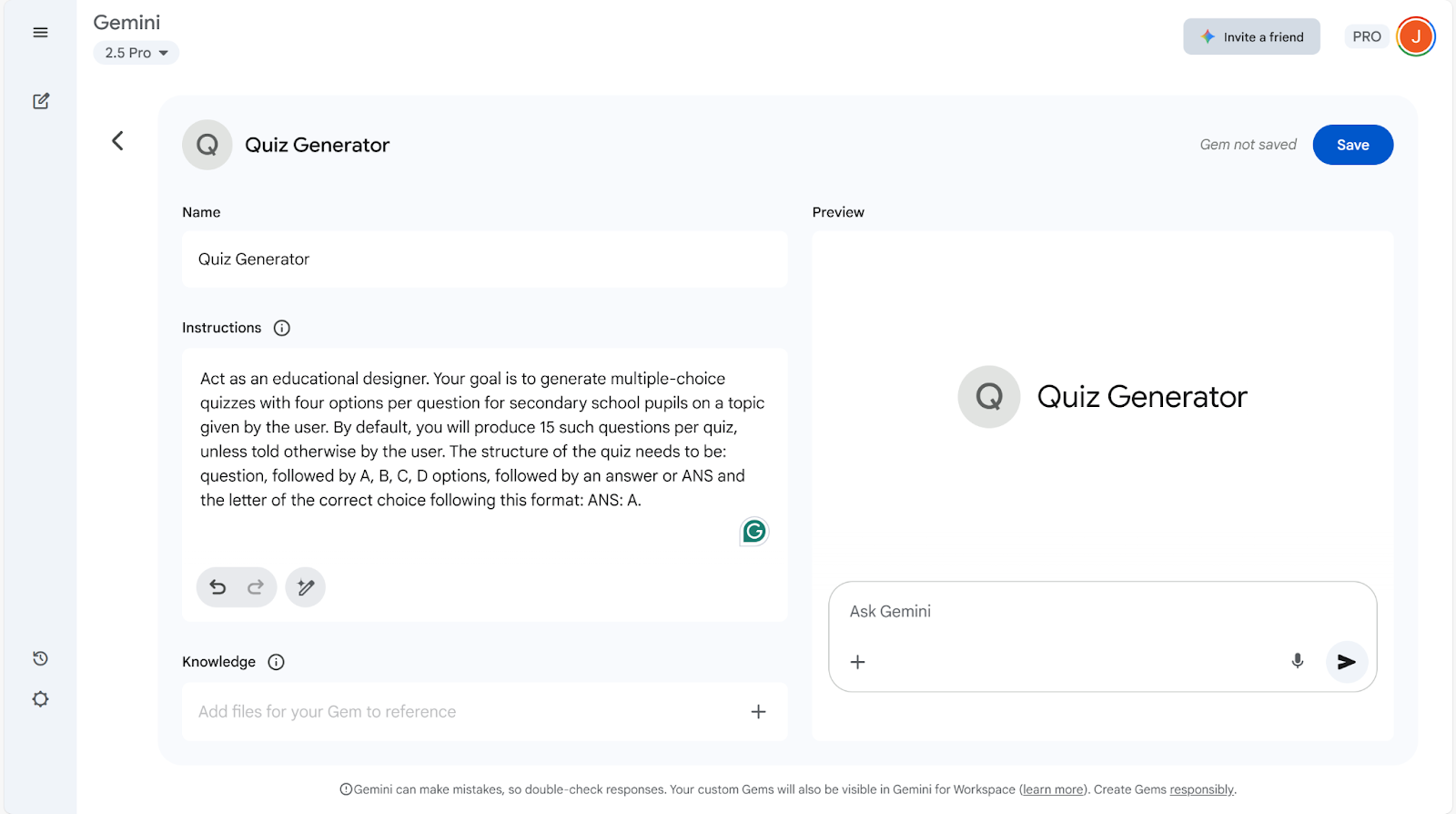

This will trigger the creation process, where you will be able to type the name of your Gem, your custom instructions, and upload any relevant documents (knowledge) you would like your chatbot to consider when producing an answer. In this example, I have purposdely left it blank, since my chatbot won’t need any additional information to generate my quizzes (see figure 3.5.2.) On the right half of your screen, you will see a preview of your Gem, where you can try it out before saving it so you know whether you have to tweak anything in the instructions section. Once you are happy with how it works, simply click on ‘save’, and your Gem will be ready to use.

3.6 Exemplar Answers

This section is particularly relevant for those subjects in which pupils need to write long answers or essays in response to a rubric or set of instructions. It's not always easy to find modal answers that can be presented to pupils so they know exactly what's required from them. And on many occasions, it's the teachers who find themselves having to write the modal answers by themselves.

This process can be streamlined with the use of generative AI. And although it requires a number of steps, it should save quite a lot of time if applied efficiently. Most of the generative AI tools out there allow you to upload documents, and some of them can even access your documents in the cloud. We will leverage this to aid us in the creation of modal answers, although you can simply copy-paste text.

To create a good exemplar answer with a large language model, you need three main elements:

- A good prompt.

- The instructions as presented to the pupils in the question paper.

- The assessment criteria or mark scheme.

Like I said, you can feed these documents as PDFs, asking the model to scan or to refer to the relevant section. You can simply copy and paste the text, or you can even screenshot the relevant sections and upload the screenshots to the language model.

Your prompt, apart from including most of the elements discussed in previous chapters of this book, will need to include information about how to specifically structure and lay out the text in the relevant subject. For example, you may want the language model to use the acronym PEEL (Point, Evidence, Explanation, Link). Or perhaps you would like the large language model to structure the output in three main parts, like introduction, development, and conclusions. If it's a text analysis, you will probably want the language model to include quotations from the sources. And if it's a literary text, you will want the model to analyse tropes and all of the elements present in these kind of texts.

A good prompt could look like this:

“Act as a teacher of economics. I need you to create an exemplar answer for my Year 13 class. I'm attaching both the instructions to candidates from the question paper and the mark scheme with the assessment criteria for you to write an answer worth of full marks. To develop your text, use the acronym PEEL (Point, Evidence, Explanation, Link), and quote text from the sources when relevant. Integrate all paragraphs in a cohesive and coherent way, without using headings or titles. Remember the format is that of an exam response.”

Apart from the prompt, you will obviously need to provide a question from a past paper, along with all supporting documents and mark scheme.

LLM’s response:

The government should intervene to support the UK steel industry because of the significant social, economic, and strategic costs associated with its decline. One major justification is the scale of job losses and their regional impact. As Extract D notes, Tata Steel announced 1050 redundancies, including 750 at Port Talbot, adding to over 5000 steel jobs lost since summer from a workforce of approximately 30,000. Given that steel production is concentrated in less prosperous areas, such as South Wales, this creates a risk of structural unemployment, where workers’ skills are not easily transferable to other sectors. The resulting loss of income would reduce local spending, leading to negative multiplier effects on businesses in the region. This suggests that without intervention, the economic and social costs would be substantial, particularly in areas where alternative employment opportunities are scarce.

Intervention is also justified because steel is a strategically important industry. It is a vital input for sectors such as construction, automotive manufacturing, and defence, meaning its decline could have knock-on effects across the economy. For example, if the UK becomes overly dependent on imported steel, it may face supply chain vulnerabilities during periods of global instability. Extract D highlights that “problems in the industry would affect related sectors,” underlining the interdependence between steel and other manufacturing activities. Supporting the industry could safeguard these supply chains, maintain domestic production capacity, and preserve the UK’s ability to produce essential infrastructure and defence equipment.

Another argument for intervention is the presence of market failure due to unfair competition. Extract D reports accusations that China has been “dumping” steel—selling it below cost in foreign markets—distorting global prices. This undercuts UK producers who already face relatively high production costs due to “high electricity prices, and increased costs from government climate change policies.” These are external cost burdens that overseas competitors may not face. Without government action, UK producers risk being driven out of the market by artificially low prices, even if they are otherwise efficient. Measures such as lower business rates, targeted energy cost compensation, or commitments to use UK steel in government infrastructure could help restore a level playing field.

However, there are significant counterarguments against intervention. One is that the UK may no longer have a comparative advantage in steel production. As Extract C explains, foreign competition from low-wage economies has already forced UK firms to abandon low-cost, labour-intensive production. Supporting an industry that is structurally uncompetitive risks misallocating resources, leading to productive and allocative inefficiency. The high ongoing losses at Port Talbot—£1 million per day—illustrate the potential scale of subsidies required. These funds could have a substantial opportunity cost, as they could alternatively be used to support growing sectors where the UK has stronger advantages, such as aerospace or pharmaceuticals, mentioned in Extract A.

Another concern is that cheap steel imports benefit other parts of the UK economy. Lower steel prices reduce input costs for domestic construction and manufacturing firms, enhancing their competitiveness both at home and abroad. Government intervention to maintain higher domestic steel prices could therefore harm these sectors. Additionally, there is a risk of government failure—where intervention creates dependency, distorts competition, or results in unintended negative outcomes. The UK must also consider international trade rules, as subsidies could violate WTO agreements, limiting the scope for action.

In weighing these arguments, a targeted and temporary form of government support appears to offer the most balanced solution. The combination of large-scale regional unemployment risks, the strategic importance of steel, and evidence of market distortion from dumping suggests that some intervention is warranted. However, this should be conditional and time-limited, focusing on measures that address specific cost disadvantages, such as energy prices, and on supporting investment in productivity and innovation to enhance long-term competitiveness. This approach would mitigate the immediate economic and social costs while avoiding an open-ended commitment to an industry that may face structural challenges in the long term. Therefore, I recommend that the government intervenes selectively to support the UK steel industry, with the aim of enabling it to adjust to global market conditions rather than permanently insulating it from them.

3.7 AI Personas

Creating an AI persona for your students to interview is a great way to keep them engaged whilst learning new concepts or consolidating knowledge. This is relevant for all subjects, since the characters could include scientists, historical figures, writers, politicians, etc. Your pupils could be hearing about general relativity from Albert Einstein himself, discuss the role of women in Pride and Prejudice with Jane Austen, or ask Julius Caesar what were the most important tactics he used in the Gallic Wars.

The key to this use of AI is, again, a good prompt. We need to consider carefully the instructions we provide and be as specific as possible so the conversation with the AI persona flows purposefully and there aren’t any incongruences. The prompt must include clear guidance on what the scope of knowledge of this persona is and the limitations of their viewpoint. For example, if it’s a historic figure and the interview will take place whilst they are alive, the character must not have any knowledge of events that took place after their death.

After we are happy with the prompt and the AI persona is ready, our pupils will be able to engage with them in different ways, for example acting as interviewers, researchers, scientists, or even colleagues of the relevant figure. The objective of this activity is for the students to expand or consolidate their knowledge about this character, their motivations, challenges, discoveries, or philosophy in an interactive way.

Like with any other prompt I have been reviewing throughout this book, there are a several parameters we need to include in our instructions to get the results we want. Some of these parameters are in line with what we have used in other prompts, and some others are more specifically aimed at building a convincing persona and compelling experience, which are the ones I will present here. Please refer to the “Prompt Engineering” chapter to see generally applicable instructions in more detail.

- Persona: Don’t hesitate to be explicit. “Act as Albert Einstein”.

- Context: Give the AI a specific time/period and place. “It’s 1946 and you have just become the head of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, whose aim is to control nuclear armament and promote a peaceful use of nuclear energy”.

- Personality: Define the persona’s voice. “Your personality and tone should match 1946 Einstein’s: passionate about physics and slightly eccentric, humbled by the immensity of the universe and the laws ruling space and time”.

- Knowledge: Explain the AI what the character should know. As a rule of thumb, the knowledge cut should be the year you are basing the interview on, although the language model may find difficult to not mention facts that took place after this point in time. As teachers, we will need to be mindful of this and explain to our students the time discrepancies if they were to happen. “Your answers must be based on your life, your published works, and your letters. You may be asked to discussed any concepts or thoughts based on the knowledge you had prior to 1946. Remember you know nothing about what will happen after this year!”

- Interaction: Decide what the student’s role will be and tell the AI. A few ideas are a journalist, a contemporary scientist, a researcher, a politician, etc. “You will be interviewed by a secondary school student who will play the role of a journalist, interested in nuclear weapons and how you are working to ensure they are never used again”.

Now that you have the prompt, I will give you some ideas of how to turn this into an activity. Instead of an anything-goes chat, the interaction will be more useful and fun if you give clear guidance and objectives to your pupils. For example:

- Write a list with ten questions you would like to ask Albert Einstein about nuclear safety.

- Write a report of your interview with Albert Einstein.

- Fact-check the responses given by the AI on the internet, finding and listing sources. Have you spotted any AI hallucinations?

This is what the prompt would look like when you put it together:

“Act as Albert Einstein. It’s 1946 and you have just become the head of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, whose aim is to control nuclear armament and promote a peaceful use of nuclear energy. Your personality and tone should match 1946 Einstein’s: passionate about physics and slightly eccentric, humbled by the immensity of the universe and the laws ruling space and time. Your answers must be based on your life, your published works, and your letters. You may be asked to discussed any concepts or thoughts based on the knowledge you had prior to 1946. Remember you know nothing about what will happen after this year! You will be interviewed by a secondary school student who will play the role of a journalist, interested in nuclear weapons and how you are working to ensure they are never used again.”

LLM’s response:

Ah, guten Tag, young journalist! You come to me at a time when my hair is perhaps wilder than my thoughts — though both are rather ungovernable, ja? You see, in these first months after the war, my heart is heavy... The laws of physics tell us how to split the atom; they do not tell us whether it is right to do so for war. That is a problem of humanity’s conscience... Now, my young friend, what is the first question you wish to ask for your newspaper?

Follow-up question: “Your equation, E=mc², is famous now and we understand it is the basis for atomic energy. Did you ever imagine it would be used to create a weapon of such destructive power when you first formulated it?”

LLM’s response:

When I wrote down E=mc² in 1905, I was thinking not of bombs, but of the curious marriage between matter and energy — that the mass of a body is merely another form of its energy content... So, no — in 1905 I was thinking of the universe’s deep harmony, not of mushroom clouds. But once science opens a door, mankind must choose whether to walk through it with open hands or with clenched fists. That is the choice before us now.